Speculative Analysis and Correlation Study on the Cyber Operations Capability Spectrum Underlying the US Military Invasion of Venezuela

The original report is in Chinese, and this version is an AI-translated edition.

Background

On the early morning of January 3, 2026 local time, the US military invaded the capital of Venezuela, Caracas, and targeted multiple targets. They forcibly took control of Venezuelan President Maduro and his family and transferred them to the United States. According to sources from all sides, this operation involved the deployment of a large number of air forces by the US from around the world (approximately 150 fighter aircraft), including early warning aircraft, bombers, fighter jets, electronic warfare aircraft, helicopters and drones, etc. The Delta Force was responsible for the ground operation[1]. Currently, the details of the operation are limited in terms of available information. Especially regarding the cyber intelligence and offensive and defensive operations, only “phrase level” reference information is currently available. There are already many detailed process summaries circulating on the internet, including the detailed parts related to network activities and intelligence analysis. Most of them are the result of AI aggregation. Although they have formed certain reference information correlations, there are also many illusions, distractions and misleading elements. Therefore, the Antiy Strategic Intelligence Center and the Antiy Computer Emergency Response Team (Antiy CERT) attempt to conduct relatively cautious analysis based on our historical research on the relevant actors, starting from the behavioral patterns of the corresponding actors, and based on capability system assessment and inference.

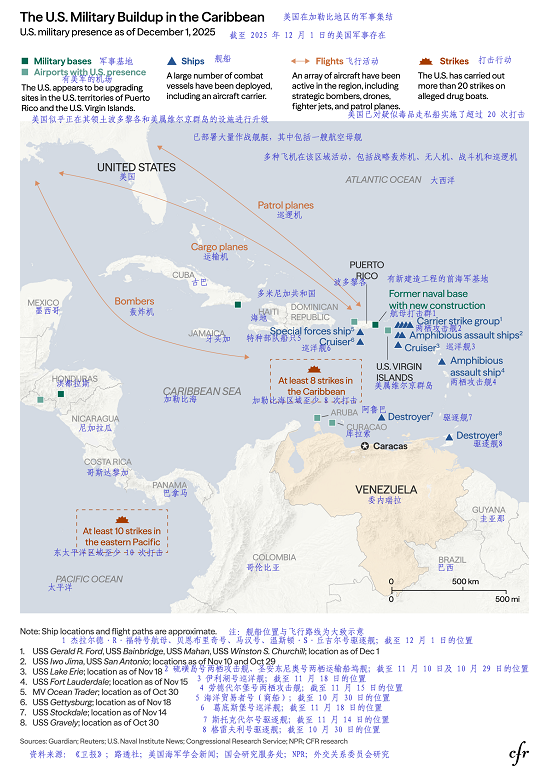

Figure 1. U.S. Military Build-Up in the Caribbean[2]

(Image source: Council on Foreign Relations, translated by Antiy)

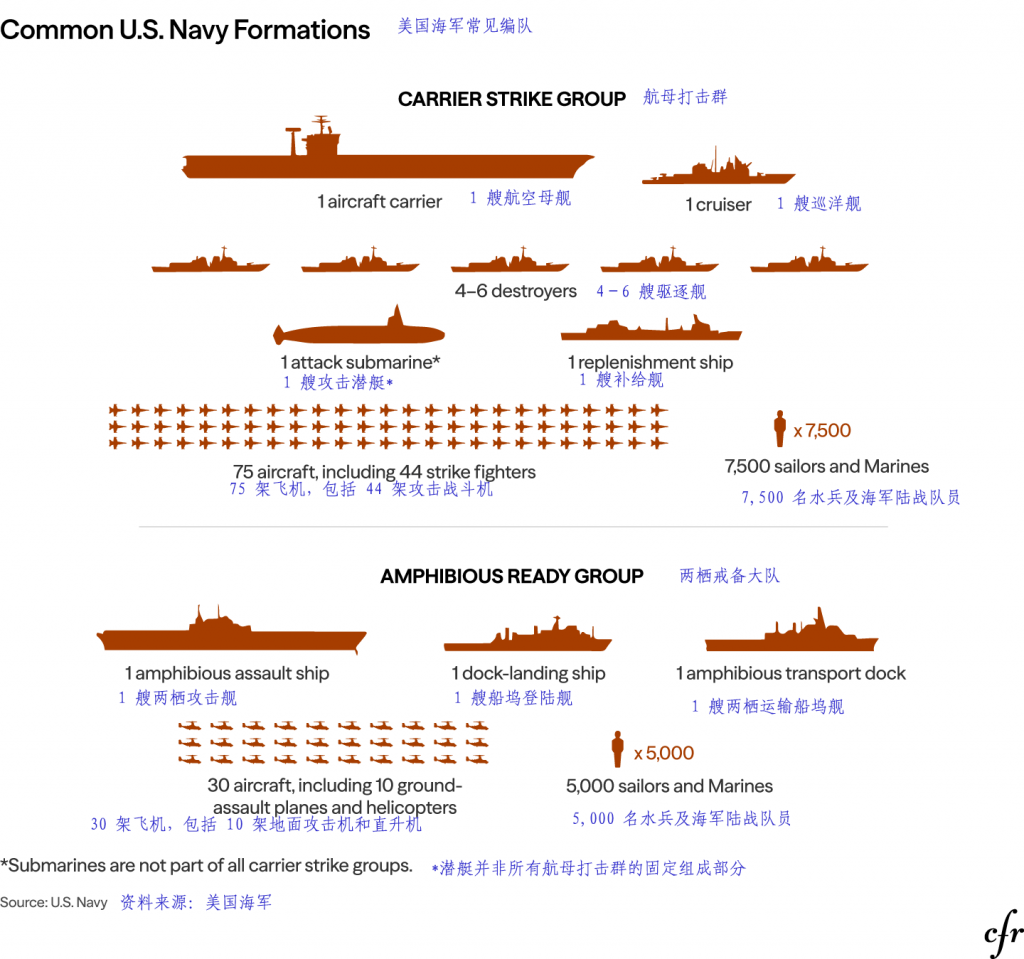

Figure 2. Common U.S. Naval Formations

(Image source: Council on Foreign Relations, translated by Antiy)

The most verifiable information from the US currently comes from President Trump’s hint at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago on January 3, stating that “we used technical expertise to disable power in Caracas”. Currently, most global observers speculate that Trump’s “expertise” refers to a “cyberattack”. Meanwhile, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Dan Caine confirmed the involvement of US Cyber Command in the operation. Other related information comes from reports and speculations by the internet monitoring organization NetBlocks, which uses partial network outages in Venezuela as evidence of the blackout, but does not confirm that the blackout was caused by a cyberattack, nor that the regional network disruptions were a consequence of the blackout. Therefore, we can only extrapolate and speculate on the US’s activities in the cyberspace in this incident based on its historical activities in Latin America, its cyber military operational paradigm, and its capability system, and analyze the combined effectiveness of its cyber operations and physical warfare. However, we also want to point out that given the high degree of invisibility and asymmetry of cyber operations, for geographical locations inaccessible to technical perception capabilities, the main focus of analysis should be on assessing the capabilities of cyber actors and extrapolating paradigms.

Based on these analyses, we believe that:

From a tactical perspective: Cyberspace Exploitation (CE) in cyberspace constituted an important (but not necessarily decisive) intelligence layer in this operation, playing a crucial cross-verification role in intelligence convergence and analysis. Cyberspace Attack (CA) may have acted as a temporary disruption of power supply, thereby maximizing security cover for the US military operation. It cannot be ruled out that the U.S. attempted to disable the adversary’s air defense weapon systems through cyberattacks during this operation.

From a strategic perspective: This operation was a sudden event superimposed with inevitability, and it is a product of the neo-Monroe Doctrine under the trend of the United States’ “defensive strategic contraction” (as described by Mr. Zhang Wenmu).

1. Historical Cyberattacks by the United States Against Latin American Countries and Related Reports

Intelligence capabilities have always been a cornerstone of American hegemony, and U.S. cyber intrusions and surveillance targeting the world are a crucial component of these capabilities. Latin American countries, which the U.S. considers its “backyard”, are a primary focus of its intelligence operations. While there is a wealth of information and reports about cyberattacks against South American countries, much of this information remains speculative and based on fear, because these countries generally lack strong cybersecurity capabilities, independent industries, and the technical ability to “grab the hand of U.S. intelligence agencies”.

Among these historical incidents, particular attention has been focused on allegations of attacks targeting energy infrastructure and prominent political figures. The main events that were accused or reported include Ecuadorian President Correa’s claim in 2014 that his personal account was attacked by a U.S. server; a large-scale blackout across Venezuela in March 2019, in which Venezuela accused the United States of launching a cyber attack; large-scale blackouts in Argentina, Uruguay and other South American countries in June 2019; and on December 15, 2025, prior to this operation, Venezuela’s state-owned oil company (PDVSA) reported a “cyber attack” aimed at disrupting its operations[3]. The statement emphasized that the attack was only aimed at the administrative system. Former U.S. officials and cybersecurity experts analyzed that the attack had the characteristics of a U.S. cyber command operation. Regarding the Venezuelan blackout in March 2019, Antiy formed a joint analysis group with domestic power companies to conduct analysis and published a report entitled “Preliminary Analysis and Reflections on the Large-Scale Blackout in Venezuela”[4], which analyzed Venezuela’s power system in a relatively complete manner, investigated various possibilities, and concluded that the United States had relevant motives and capabilities, but lacked evidence to support whether it directly launched a cyber attack.

The most substantiated evidence regarding US cyberattacks on Latin America comes from intelligence leaks made by the US itself. Among the intelligence leaked by “Shadow Brokers”, it was revealed that the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) had targeted Latin American financial infrastructure to obtain financial intelligence. The primary target was BCG (Business Computer Group), a key regional partner of the financial institution EastNets, located in Venezuela and Panama. Documents indicate the NSA employed two malware tools: “SECONDDATE”[5] (Chinese name: “二次约会”) and ‘IRONVIPER’ (Chinese name: “铁蝰蛇”). The former is a backdoor mainly deployed on target network boundary devices, such as gateways, firewalls, and boundary routers, to covertly monitor network traffic and accurately select specific network sessions for redirection, hijacking, and tampering as needed. As for the latter, Antiy CERT currently only knows its equipment code name, but has not obtained the physical documents and related information. It is speculated that it may be a backdoor or traffic forwarder for the front-end targeting boundary devices similar to “SECONDDATE”, or a port injection or ferret device similar to “COTTONMOUTH”. Relying on the relevant equipment, the US launched a front-end attack, realizing a progressive penetration/traffic forwarding based on the network topology, and planned to eventually reach the SAA server to obtain information, but the relevant attack may not have made progress for some reason. In the same wave of attacks, the US attack on EastNets headquarters (located in the UAE) was successful. Antiy CERT conducted a detailed analysis in its report, “Retrospective Analysis of the Equation Group’s Attack on SWIFT Service Provider EastNets”[6]. Comparing the results of the two target scenarios also effectively illustrates that even with the US’s possession and abuse of its upstream industry and dominant advantages, its attacks on high-value deep targets still require a “lock picking and jimmying” process. It is not, in fact, “omnipotent”.

Figure 3. Cyber Operations Plan Against Venezuela and Panama’s BCG Leaked by “Shadow Brokers”

In addition to cyberspace attacks, the United States has also been confirmed to have conducted long-term surveillance and eavesdropping on Latin America in the field of intelligence signals. A report from Brazilian media in July 2024[7] revealed that the US government had been monitoring Brazilian President Lula and his advisors for 50 years, and pointed out that the US had also hacked into the network of Petrobras. More than 800 documents from US government departments show that the US government has been monitoring Lula for more than half a century, including Brazilian military plans and information about Brazilian oil production. The large-scale US surveillance activities in Latin America are a manifestation of its long-standing “Monroe Doctrine” hegemonic thinking that regards Latin America as its “backyard”, in order to gain political, military, economic and diplomatic advantages and maintain its hegemonic status.

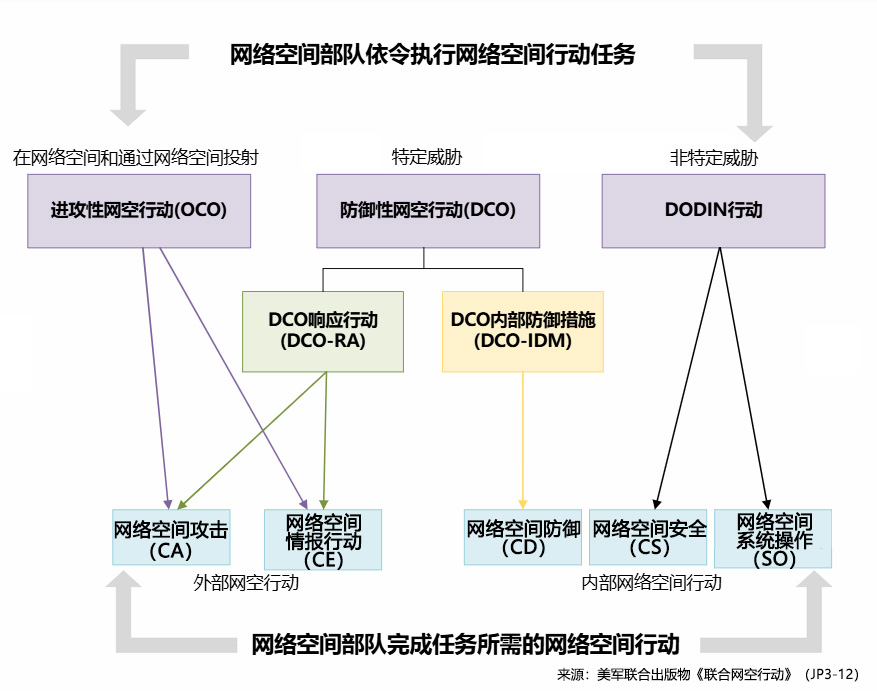

2. CE+CA: The Paradigm of U.S. Cyber Operations

Because cyberattacks are targeted and cyber weapons are often “ineffective upon exposure”, intelligence-level and information warfare-level analysis of cyberattack activities, especially those targeting external events, inevitably requires speculation based on limited information clues combined with open-source intelligence. In-depth empirical analysis typically suffers from significant delays. Currently, while sentiment-based analysis of attacks by politically biased civilian groups and verification based on cyber mapping can serve as peripheral evidence, they are insufficient to reveal the true nature of the actions.

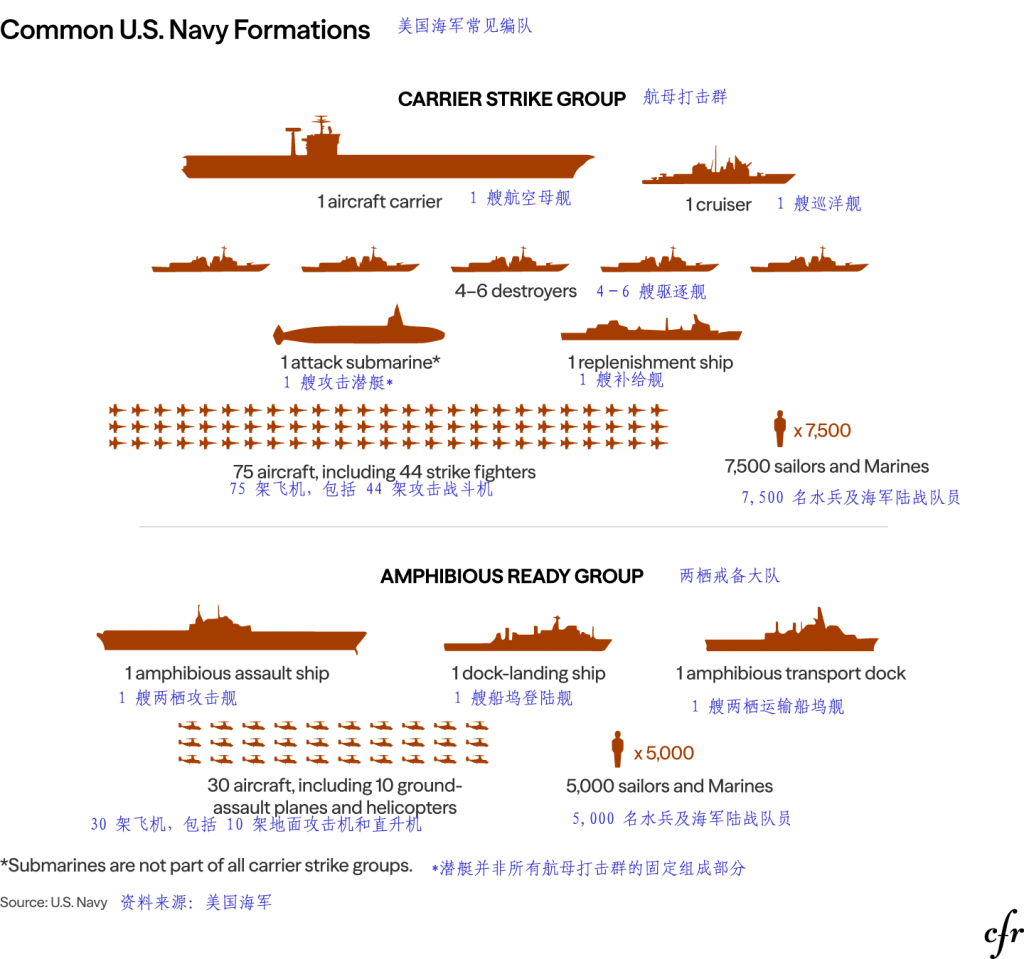

When analyzing U.S. actions, it is necessary to deeply understand their operational concepts and behavioral paradigms, and to make judgments in conjunction with relevant target and mission milestones. The U.S. military divides cyberspace into “internal cyberspace” and “external cyberspace”. Based on internal cyberspace, the U.S. military defines three types of operations: Cyberspace System Operations (SO), Cyberspace Security (CS), Cyberspace Defense Defense (CD) corresponds to basic IT operations, constraining and shaping the vulnerabilities and exposures of information systems, and interacting with threat behaviors, aiming to protect the availability, integrity, and security of one’s own networks. Regarding external cyberspace, the U.S. defines two operational styles: Cyberspace Exploitation (CE), Cyberspace Attack (CA). It is of particular concern that the U.S. strictly distinguishes between CE and CA. In the U.S.’s understanding, low-impact operations such as intruding into network systems, delivering malicious code executables, gaining system privileges, achieving persistence, and obtaining information and data all fall under the category of cyberspace intelligence operations; only operations that need to be transformed into physical and social impacts are considered “cyberspace attack” by the U.S.

The U.S. military joint publication Joint Cyber Operations[8] (JP3-12) defines CE and CA as follows:

Cyberspace Exploitation (CE): CE is a key component of Offensive Cyber Operations (OCO) and Defensive Cyber Operations-Response Action (DCO-RA), and these operations do not produce direct cyberattacks. The operations primarily include: establishing access privileges, military intelligence activities, cyber maneuvering, information gathering, and other enabling actions necessary for future military operations. The operations aim to gain and maintain cyber superiority, supporting operational environment preparation for current and future operations. Specifically, this includes: acquiring and maintaining unauthorized access to adversary networks, systems, and nodes of military value; maneuvering to advantageous positions in cyberspace; and deploying cyber capabilities to facilitate subsequent operations. When certain CEs have no other reasonable explanation or purpose than supporting a subsequent cyberattack, they should be considered a preparation phase for that specific attack. CE supports current and future operational operations through systematic information gathering, primarily including: mapping the topology of red and gray cyberspace to enhance situational awareness; identifying system vulnerabilities; supporting joint intelligence environment preparation, threat warning, and joint target development; and providing intelligence assurance for the planning, execution, and assessment of military operations throughout the operational environment.

Cyber Attack (CA): CA creates a clear denial effect (degradation, disruption, or damage) in cyberspace, or manipulates the system through cyber means, leading to denial consequences in the physical domain. Such actions constitute a form of firepower and, when authorized, can be carried out as part of an OCO or DCO-RA. Operations should be coordinated with U.S. government agencies to avoid mission conflicts and closely integrated with planned firepower in the physical domain. CA includes two forms: first, denial attacks, which prevent access to, operation of, or availability of a target system or function to a specific degree within a specified time, manifested as degradation, disruption, and damage; second, manipulation to produce physical effects, which involves manipulating enemy information systems through deception, forgery, alteration of instructions or control systems to induce denial consequences in the physical domain. These effects may be difficult to detect immediately, as the target system may still appear to be functioning normally on the surface. Such attacks may reach the threshold of international law for “use of force” or “armed attack”, especially when they aim to cause physical damage or fatal consequences.

Figure 4. U.S. Definition and Behavioral Patterns in Cyberspace

(Image source: Joint Cyber Operations (JP3-12), a joint publication of the U.S. military, translated by Antiy)

While both CA and CE fall under the category of “external cyberspace operations”, they differ significantly. CA aims to create a perceptible denial effect on target networks or physical facilities through degrading, disrupting, damaging, and manipulating systems; it is an active pressure or destruction operation and part of OCO. CE, on the other hand, focuses on acquiring adversary network intelligence without producing obvious effects, through covert access, information gathering, and vulnerability identification. This intelligence supports situational awareness, joint target development, and operational planning, thus empowering military operations. Only when CE actions have no other legitimate purpose than supporting a specific attack is it considered part of the preparation phase for that attack. Although they differ, they are closely linked in the operational chain. However, CE has already achieved penetration and persistence; whether it involves long-term covert acquisition or transforms into disruption and paralysis depends on the pre-set or received execution of different instructions.

In this US military operation to invade Venezuela, the US comprehensively utilized both CA and CE methods to achieve integrated operational effectiveness and multi-domain coordination. CE was manifested in the continuous conduct of covert intelligence operations, the convergence and cross-verification of multi-source intelligence, and the precise location and real-time monitoring of high-value targets. CA was manifested in the implementation of CA methods on the Caracas power system, cutting off the operation of critical power infrastructure and “clear the operational path” for subsequent US air strikes and special operations.

3. CE in Action: Cyberspace Intelligence Activities Serving Operational Missions

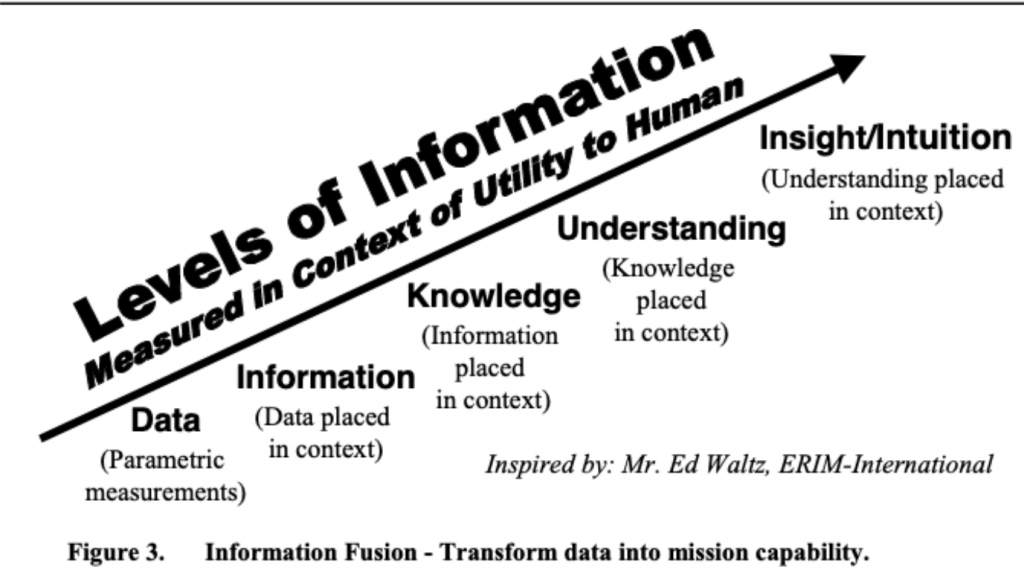

The U.S. military introduced the concepts of data information and fusion in its 1999 F2T2EA Kill Chain model, proposing that “data sets the scene to become information, information sets meaning to become knowledge, knowledge sets insight to become intelligence, and intelligence sets intent to become decision”. This approach relies heavily on multi-source intelligence fusion, seamless cross-domain coordination, and high-speed information flow. It can be concluded that prior to this special forces deployment, the U.S., relying on an intelligence cycle-driven, full-source intelligence fusion mechanism, had built a multi-layered intelligence coverage system around key targets such as Maduro through long-term, continuous forward intelligence infiltration and target network analysis. This resulted in highly transparent control over their movements, security structures, and decision-making environment, shaping the battlefield for subsequent special operations.

Figure 5. The U.S. Military’s Definition of Data-to-Mission Transformation

U.S. intelligence analysis applications are classified into five categories according to their sources: geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT), and open source intelligence (OSINT). The first four types of intelligence are obtained by the responsible intelligence agencies through special technical means (including relying on reconnaissance equipment, espionage activities, and network intrusion to steal information). Open source intelligence is a common intelligence means used by all agencies in the U.S. intelligence community. It is used in conjunction with other technical intelligence. These intelligence means have a certain degree of overlap, can be converted into each other, and can also support and verify each other. The relationship between them is shown in the illustration of the RAND Corporation’s 2018 report, “Defining Second Generation of Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) for Defense Enterprise”[9].

Figure 6. Five Categories of U.S. Intelligence and Their Logical Relationships

It can be concluded that the US operation leveraged its abundant intelligence and synergistic effects. While Venezuela possesses a certain degree of geographical depth, most of its cities—including the capital Caracas—are mainly located in the northern coastal areas. Both the Presidential Palace of Palacio de Miraflores (situated in the city center) and the fortified residence within Fort Tiuna Military Base in southern Caracas, where Maduro was arrested this time, are within a straight-line distance of 30 kilometers from the coastline. The U.S. military’s strategic forward nodes on the Dutch islands of Curaçao and Aruba are 60 kilometers and 27 kilometers away from Venezuela’s coastline respectively. In the Caribbean Sea, the U.S. has deployed a combat strike group centered on the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford and an amphibious task force built around the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima, the latter of which is capable of launching and recovering helicopters and F-35C vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) fighter jets. Caracas is within the direct strike range of both US task forces. In addition to island reconnaissance facilities, the EA-18G Growler electronic warfare aircraft deployed in this operation have an effective jamming radius of 150-250 kilometers and a detection range of 300-500 kilometers (for strong signal sources). It is clear that Maduro’s every move is completely within the effective coverage of various US military reconnaissance technologies. Furthermore, the increased use of US reconnaissance satellites, drones, and other means has created a comprehensive coverage of military intelligence.

Figure 7. Venezuela’s Capital Is a City on the Caribbean Coast

With the overlay of signal reconnaissance intelligence from space, air, and sea, along with human intelligence, strike decisions can be effectively supported. Cyber intelligence further serves as verification and corroboration of these methods. Meanwhile, in situations with obstructions or electromagnetic interference in space, targeted cyber intelligence activities by the US, leveraging penetration and implantation capabilities, can achieve tactical objectives that are difficult to accomplish through other intelligence methods.

The U.S. cyber intelligence capabilities rely on several key support points to build a globally leading and systematic intelligence advantage. The U.S. cyber intelligence activities supporting the Venezuelan operation can be broadly divided into four levels: information acquisition, attack and penetration, and intelligence aggregation and analysis.

First, it is based on the information acquisition capability of secret cooperation with large US IT/Internet companies[10]. The global information acquisition based on industry is an important support for the US cyberspace intelligence capability. It is based on the US industrial advantages and the coupling relationship between enterprises and US intelligence agencies, which constitutes a unique advantage that is difficult for other countries to replicate. Its most famous technical interface mechanism is the “PRISM” project. According to the documents leaked by Snowden, in 2004, the US government launched the “STELLARWIND” project to carry out large-scale surveillance and intelligence collection activities. Later, “STELLARWIND” was split into four projects: “PRISM”, “MAINWAY”, “MARINA” and “NUCLEON”, which were implemented by the NSA. The “PRISM” project is a top-secret intelligence collection operation that has been implemented since 2007. The main method is to rely on the US’s dominant position in the global Internet infrastructure and digital service fields and use the data interfaces provided by US telecommunications operators, Internet service providers and large IT companies to carry out large-scale and normalized information acquisition. “MAINWAY” and “MARINA” projects store and analyze trillions of “metadata” on communications and the internet, respectively. “NUCLEON” project intercepts the content and keywords of telephone conversations. Compared to “MAINWAY” and “MARINA”, “NUCLEON” project focuses more on acquiring content information, using intercepted calls and locations mentioned by callers for routine monitoring. “PRISM”, along with these intelligence-gathering projects, constitutes a systematic intelligence operation capability, enabling US intelligence agencies to create comprehensive profiles of global internet targets, including personnel, channels, and devices, thereby forming a relatively accurate target location and intelligence extraction capability.

Second, it is based on the organization of teams, engineering support systems and equipment attack and penetration capabilities[11]. In the field of cyberspace security, the United States relies on a well-organized network attack team, a huge support engineering system and a standardized attack equipment library, a strong vulnerability collection and analysis mining capability, as well as related resource reserves, systematic operating procedures and manuals to build a cyberspace operation capability with the characteristics of equipment system covering all scenarios, vulnerability exploitation tools and malicious code payloads covering all platforms, and persistence capability covering all links. It relies on a mature technical cyberspace threat framework to carry out attack capability planning, organization, arrangement and implementation, and finally realize the multi-source convergence of human intelligence, signal intelligence and cyberspace intelligence to achieve the intelligence enrichment effect. Looking back at our previous analysis of various US attack operations, the Equation Group payload can not only be deployed based on iMessage vulnerabilities, but also exploit browser vulnerabilities on the network side using the Quantum system to compromise high-value targets; the Stuxnet attack against Iranian nuclear facilities can use the “ferry” attack to penetrate physically isolated networks, or use integrated weapons to disrupt centrifuges on internal networks without external networks according to predetermined logic; attacks targeting the SWIFT financial system can achieve layer-by-layer breakthroughs in control at the border, internal network, and database, and can move freely to continuously and covertly obtain financial data; and the recently disclosed “Triangulation” operation has broken the security “myth” of the iOS system with a “zero-click” mode by using multiple system and hardware zero-day vulnerabilities; all of these cases are typical examples of the US carrying out high-precision, strategic cyberattacks in cyberspace, fully demonstrating its leading position in terms of attack complexity, technical concealment, and strategic influence.

Third is the institutionalized intelligence-sharing system (including the utilization of open-source intelligence) between the government and enterprises based on the “revolving door” mechanism. This system is a crucial support for the US’s cyberspace intelligence capabilities and constitutes its consistently leading intelligence ecosystem globally. One of the most representative practices is “Sentinel Horizon”, which we have previously highlighted in our historical analysis reports. These projects encompassed all 18 U.S. intelligence agencies, marking the first time that the threat intelligence capabilities of the U.S. private sector were fully utilized to enhance the capabilities of U.S. intelligence agencies. The project provided U.S. intelligence agencies with access to commercial threat intelligence data, regular information sharing, and expert analysis exchanges. This system is highly coupled with the use of open-source intelligence and possesses both offensive and defensive value. Its important information sources come not only from the autonomous perceptions of the sharing companies but also from a large amount of information exposed on the internet. In Section 5 of this paper, we specifically compiled information on the systemic critical data breach in Venezuela.

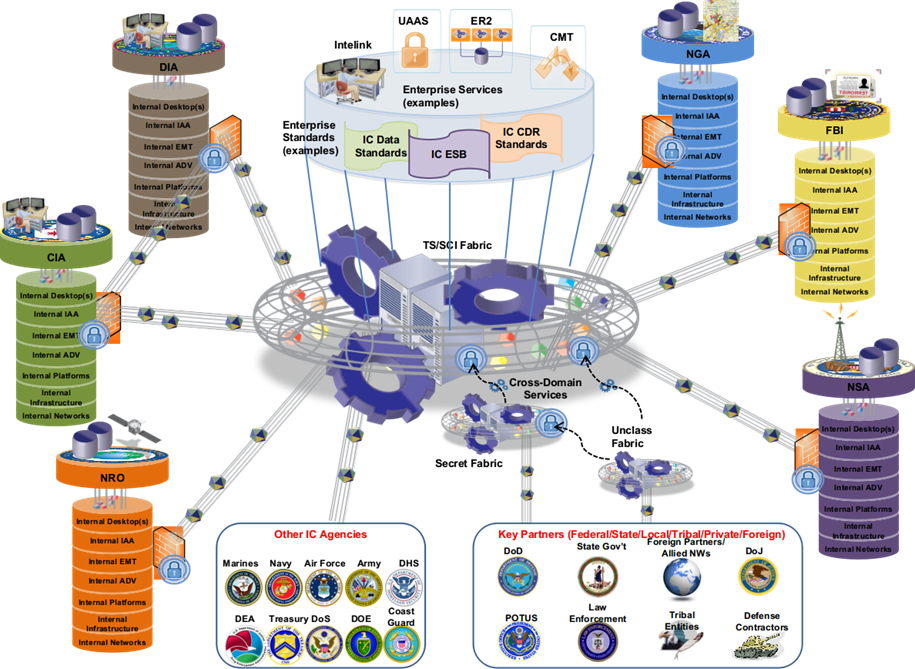

Fourthly, there is the intelligence aggregation capability based on cloud platforms such as IC ITE. The U.S. has built a large-scale intelligence cloud (IC Cloud) through IC ITE, which systematically integrates all IT resources and services of the U.S. intelligence community and Department of Defense, achieving intelligence fusion and resource sharing. As the core infrastructure of the U.S. intelligence system, IC ITE unifies all sources of intelligence, including geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT), and open-source intelligence (OSINT), into a comprehensive intelligence integration system based on big data platforms and artificial intelligence, achieving a richness effect.

Figure 8. The U.S. Achieves an Intelligence Enrichment Effect Based on a Unified Intelligence Infrastructure

Table 1. Three Primary Methods for the U.S. to Acquire Cyberspace Intelligence

| Target Means | Relevant Elements and Means | Advantage | Shortcoming | Potential Value in This Operation |

| Major U.S. Internet/IT Vendors/Operators/Upstream Organizations | • User data was obtained directly from the servers of major US IT and internet companies such as Microsoft, Google, and Facebook through projects like PRISM. • Partner with telecom operators (such as Level 3) to intercept fiber optic data. • Promote weakened encryption standards (such as ISO) | • Large data scale: Directly obtain massive amounts of user communication content • Legitimacy cover: Relying on laws or secret agreements, the operation is highly covert. • High efficiency: No complex attack process required, data acquisition in real time. | • Can only be launched with partner companies • It is difficult to directly obtain high-value data with defensive depth. • High data redundancy: Valuable information needs to be filtered out. | • It could be used to monitor Maduro and his associates’ cloud-stored emails, social communications, and information and related tracks collected by related apps. Conduct relevant personnel personality and psychological profiles, and draw personnel relationship maps. |

| Network Intrusion, Penetration, and Data Theft | • TAO department implanted Trojans using weapons such as “Quantum” and “Acid Fox”. • Exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities to attack critical systems (such as the Stuxnet virus) • Hijacking app stores (such as the “Angry Horn” project) | • Precise targeting: Allows for the implantation of malware targeting specific individuals. • High degree of concealment: Using tools such as “marble” to cover the source of the attack. • High technological deterrent: capable of remaining undetected for extended periods. | • High technical threshold: requires continuous development and updating of the arsenal • May expose attack traces: The tool becomes worthless once the security company traces the attack. • High cost: Maintaining the arsenal and vulnerability inventory requires substantial funds. | • Potentially, they could hack into Maduro’s team’s electronic devices to obtain internal information and documents. • Cut off their communication channels or monitor encrypted communications |

| Open-Source Intelligence Sharing | • Sharing signals intelligence through the Five Eyes intelligence alliance • Obtaining information by monitoring public media, news, or other data sources • Exploiting “fourth-party opportunities” to steal intelligence data | • Low cost: No need to develop sophisticated attack tools • Surface legitimacy: Can be argued as “public data collection” • Wide coverage: encompassing the dark web, deep web, and public platforms. | • Dependence on partners: Changes in the attitudes of allies may affect resource sharing (e.g., the Denmark incident sparked discontent in Europe). Information fragmentation: the need to integrate multi-source data • Limited accuracy: cross-validation required | • It is possible that Maduro’s whereabouts and latest developments were obtained through intelligence from other countries. • Analyze their hiding place based on publicly available information. |

Based on the capability analysis in the table above, it can be concluded that the US, using cyber intelligence, can achieve comprehensive intelligence coverage against key individuals and organizations in Venezuela. Its possible (or inevitable) tactical actions include:

- They infiltrated Venezuela’s critical infrastructure and information systems to obtain internal documents, materials, intelligence, and other information.

- Hacking into and controlling the mobile phones or terminal computers of key Venezuelan personnel to directly obtain information and turn these devices into mobile eavesdropping devices or springboards for further attacks.

- They hacked into the security equipment and smart home systems of key Venezuelan buildings to achieve their goal of internal reconnaissance and eavesdropping.

- The goal is to infiltrate and gain control of Venezuela’s critical infrastructure, continuously monitor its operational status, and prepare for the transformation into a CA.

4. CA in Action: Regional Power Outages Supporting Operations

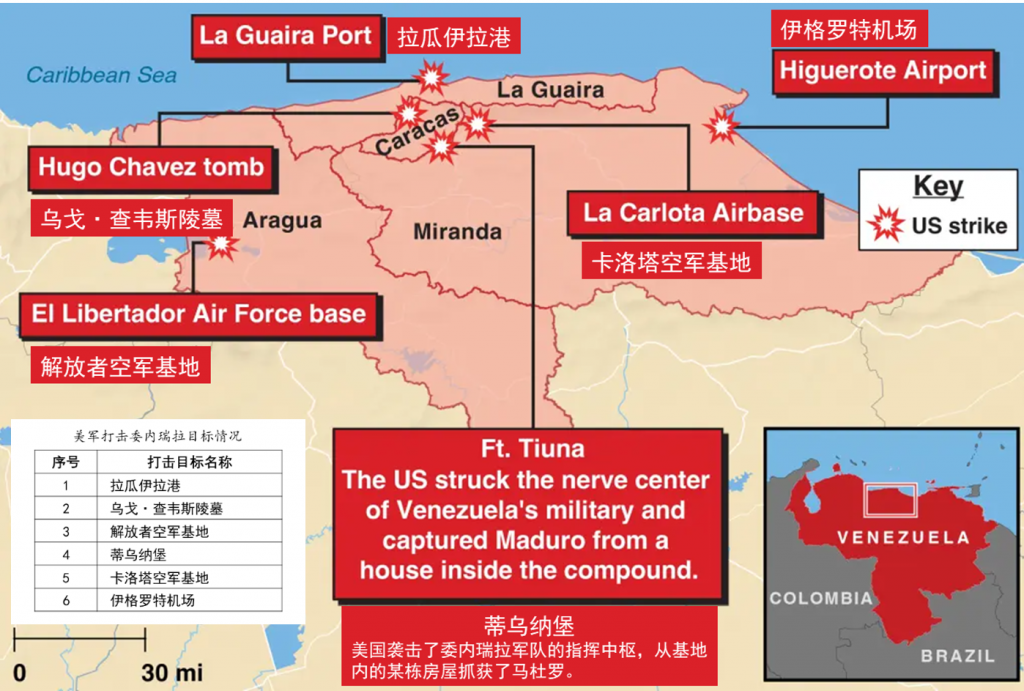

The US is conducting a highly targeted military operation. All its physical, electromagnetic, cyberspace, and cognitive spectrum activities revolve around the core objective of kidnapping and controlling the Venezuelan president, but it also seeks to gain some related value.

The U.S.has bombed multiple military targets in Venezuela, including La Guaira Port, ElLibertador Air Force base, Ft.Tiuna, La Carlota Airbase, and Higuerote Airport, all of which are military and infrastructure targets. However, according to relevant information, the targets hit by the bombings also include Hugo Chavez tomb, which is clearly a political target. It is evident that the U.S. military strikes have taken into account considerations regarding subsequent cognitive impacts.

Figure 9. U.S. Military Strikes Targets in Venezuela

(Image source: NEWYORK POST, January 3, 2026, translated by Antiy)

Figure 10. U.S. Military Bombing of Hugo Chavez Tomb in Venezuela

(Image source: X platform)

Compared to firepower strikes and special operations, the biggest concern regarding cyber operations stems from whether they were the cause of the Caracas power outage during the US military operation. Trump admitted at a press conference that the US “made almost all the lights in Caracas go out”, attributing this to “a technological advantage”. General Caine, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) of the U.S. military, also stated that U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM), and the various combatant commands have “conducted coordinated efforts to synergize and superimpose multiple operational effects”, thereby “opening up operational channels” for subsequent air strikes and special forces infiltration.This power outage is fundamentally attributed to cyberattack methods. At the same time, it is impossible not to compare it with the 2019 Venezuela blackout.

Compared to the 2019 blackout, this major power outage exhibits several differences:

First, the social context and internal conditions differ. During the 2019 blackout, Venezuela was in the midst of a severe political crisis and economic collapse. Some citizens attempted to flee the country, government forces and militias coexisted, instability existed within the military, some soldiers attempted a coup, and there were widespread street riots. Incidents such as damage to power equipment and burning of substations were frequent, suggesting a combination of factors contributing to the blackout. In contrast, while Venezuela faced more direct military pressure from the US during this blackout, the overall domestic social environment was relatively stable, with no large-scale riots or protests. Given the timing of the blackout, which closely coincided with the planned action, and the fact that power was restored within a limited time based on available information, the likelihood of the blackout being caused by fire or physical damage to power infrastructure is lower; a cyberattack is more probable.

Secondly, it features a combination of military confrontation and destructive firepower. The 2019 blackout occurred alongside a failed “color revolution”, with the blackout serving as the attack objective: to paralyze critical infrastructure and create greater social chaos. Consequently, the Venezuelan government accused the United States of using “high-tech weapons” to attack the power system. This time, the US conducted a combined operation of targeted military strikes and cyberattacks, using EA-18G “Growler” electronic warfare aircraft to release strong electromagnetic interference, severing the Venezuelan military’s command and communication links and air defense radar signals. Subsequently, F-35 stealth fighters and cruise missiles carried out precision strikes on at least 10 key targets in southern Caracas, including military facilities, air force bases, and radar stations. The overall purpose of the Caracas blackout was to provide more covert support for the low-altitude and operational entry of Venezuelan helicopter formations. What was required was precision, certainty, and controllability.

In summary, the blackout attack was intended to support and cover US military operations. Furthermore, from the perspective of US interests, having successfully controlled the kidnapping of President Maduro and his wife, the US needs to exert relatively little influence on Venezuela to create negotiating conditions for establishing a puppet government, including bringing Venezuela under US control. Therefore, the US needs to ensure that any associated damage is relatively controlled, or even reversible, in this process. This is precisely the unique advantage of cyberattacks. As Maren Leed, former senior advisor to the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, noted in paper “Offensive Cyber Capabilities at the Operational Level”[12], “cyber weapons possess unparalleled versatility, enabling their use across all military operations from engagement to high-end warfare. Because their effects are reversible, they are exceptionally suited for all phases of combat, including environment shaping, high-intensity confrontation, and target reconstruction”.

5. Frequent Leaks of Critical Information Further Demonstrate Venezuela’s Fragile and Challenging Security Capabilities

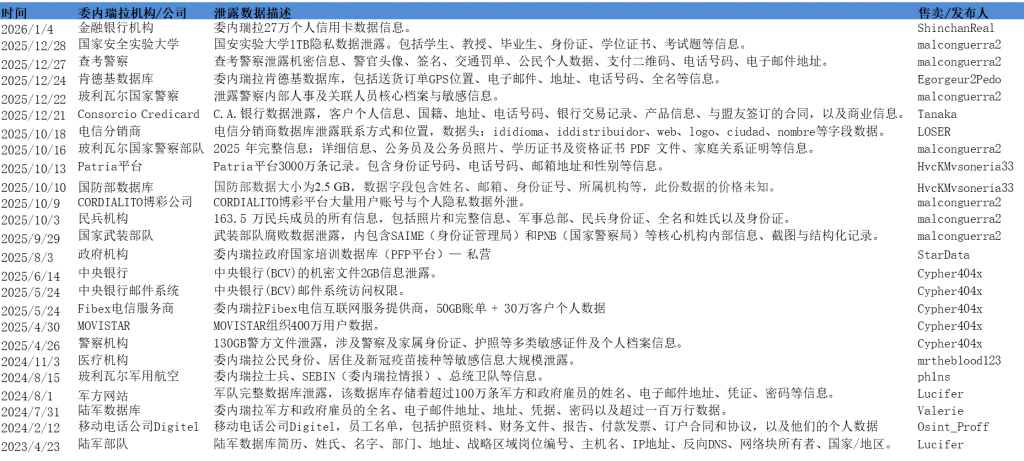

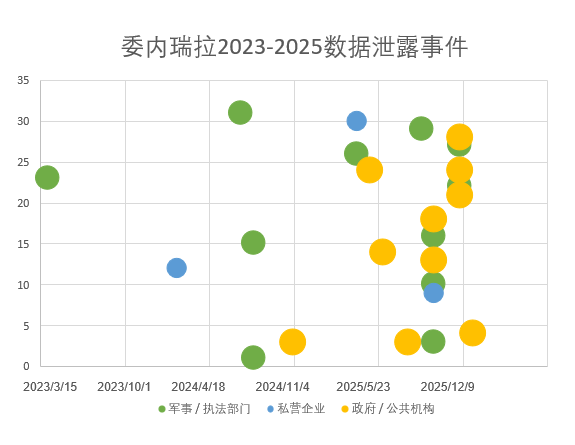

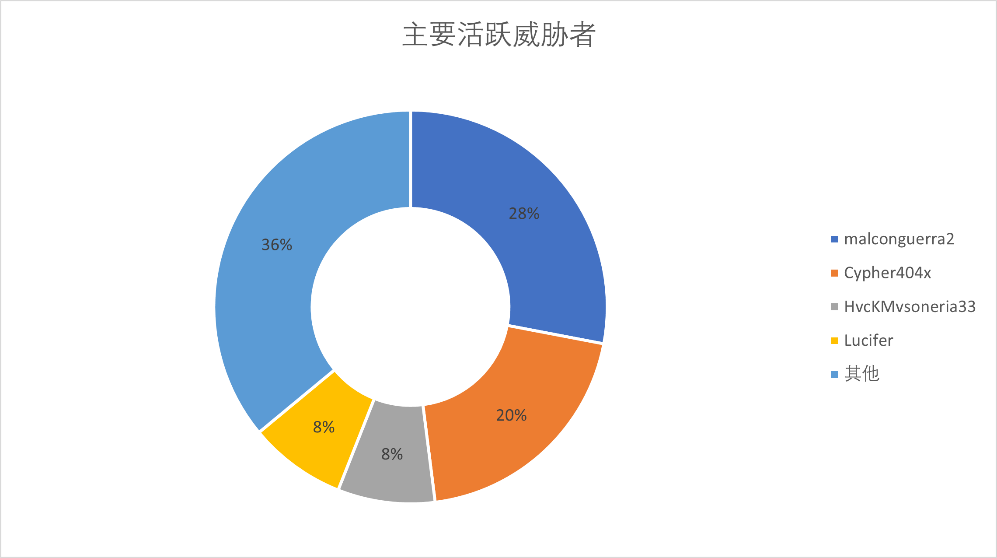

Due to the unsuitability of conducting large-scale exposure surface mapping for Venezuela, we selected Venezuelan data breaches as an indicator of its cybersecurity capabilities. Based on monitoring and analysis of the breached data platforms, Venezuelan government and business institutions suffered large-scale, systematic data breaches between 2024 and 2025. According to incomplete statistics, six major data breaches were recorded in 2024, while the number surged to 19 in 2025, more than tripling. This significant temporal distribution indicates that 2025 became a period of concentrated outbreaks of data breaches in Venezuela, with a particularly sharp increase in risk after October 2025.

These data breaches involved a wide range of organizations and involved highly sensitive data, including commercial entities such as KFC, the Credicard consortium, and telecommunications operators (such as Movistar, Digitel). More importantly, a large number of core national security and government agencies were the primary targets. For example, the Ministry of Defense, the Bolivarian National Police (PNB and CPNB), the National Experimental University of Security (UNES), the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV), and even the Patria social welfare platform covering 30 million users nationwide, as well as the detailed personal information of 1.635 million militia members, were all leaked. The leaked data ranged from personal identification cards, phone numbers, addresses, and financial records to files, certificates, family information, and internal documents of military and police personnel, and even classified military deployments and internal government communications, with the largest data volume reaching terabyte levels.

Figure 11. Summary of Venezuelan Data Breaches 2024-2025

Figure 12.Venezuelan Information Leaks Entered an Explosive Phase After October 2025

Figure 13. Exposing Key Active Threat Actors Selling Venezuelan Information

These leaked data, concentrated among a few key threat actors, could be politically biased black market organizations or simply an economic speculation by internal espionage agents. This information could further enhance the targeting of US attacks. Given the US’s formidable attack capabilities, much of this data may have already been stolen or possessed by the US, including more previously undisclosed, in-depth information. It’s even possible that some data was leaked after being acquired by the US, intended to create greater information chaos. The series of successful leaks targeting high-value objectives profoundly exposes serious deficiencies in Venezuela’s defense systems and critical information infrastructure. From military databases to national authentication platforms, multiple key nodes have been compromised or leaked internally. This in itself serves as a beacon for observing Venezuela’s cybersecurity situation and the pressure it faces, and can also indirectly indicate the targets and personnel coverage that the US can achieve through cyber operations and open-source intelligence.

6. Speculation on the Potential Impact of Cyberattacks on Weapon System Failures

Faced with this US operation, Venezuela’s air defense system failed to mount any effective countermeasure against the intruding US aircraft. IThe advanced long-range/medium-range air defense systems deployed, such as the S-300VM and Buk-M2E, did not fire a single interceptor missile. Judging from the operation’s process and effects, the fact that Venezuelan radar stations, military camps, and weapons depots were attacked by US fire is a possible reason for the air defense system’s ineffective response. Other possible factors include a significant disparity in electronic warfare capabilities leading to the suppression and blinding of Venezuela’s air defense system; the superior low-altitude penetration tactics of US helicopters making effective detection impossible; infiltration of the command and intelligence systems preventing effective interception; the existence of internal sabotage and interference; and the tropical climate affecting equipment performance.

Meanwhile, given Venezuela’s domestic military and political climate, the possibility that the military “doesn’t want to fight” or”dare not fight” cannot be ruled out. However, given the US’s multi-pronged approach in combat operations, it will not solely rely on contracts with traitors or internal saboteurs to determine operational costs; it will inevitably incorporate powerful technological means. Therefore, in this operation, it cannot be ruled out that the US employed a “Left of Launch” strategy targeting Venezuela’s weapons systems. The core logic of this strategy is to precisely intervene through non-kinetic and multi-domain coordinated means before the adversary’s weapons systems (covering nuclear, conventional, and cyber domains) achieve operational effectiveness, weakening or paralyzing their offensive capabilities at the source, preventing escalation of the conflict, or reducing defensive pressure on its own side. This strategy is widely applied in key operational domains such as air defense and missile defense, nuclear, and cyber warfare.

The US military has a long history of disrupting or even completely disabling enemy weapons. During the invasion of Vietnam, the US, through its special operations forces, conducted “Project Oldest Son”, infiltrating North Vietnam’s rear areas to replace Chinese – supplied 7.62mm rifle ammunition, 12.7mm anti-aircraft machine gun ammunition, and 82mm mortar shells with explosive trap rounds. Through the destructive effects of exploding weapons and causing casualties, and by fabricating documents after the incidents to imply quality problems with the Chinese weaponry, the US aimed to reduce Vietnamese trust in Chinese-supplied weapons and sow discord between China and Vietnam. Currently, military technology has undergone profound changes compared to the Vietnam War era. In the age of information and intelligent warfare, sabotage activities based on human intervention have become more effective, namely through cyberattacks and infiltration to achieve the goal of degrading or disabling enemy weapon systems.

In September 2013, Maren Leed, then a senior advisor on defense policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), pointed out in his article “Offensive Cyber Capabilities at the Operational Level”[12] that “when targeting a specific weapon system, cyber attacks can be launched at multiple points in time, including the early development process (which leads to weapon reliability issues) and use decisions (even if only one weapon has a problem, it will terminate the use of the entire weapon type)”, and admitted that “the significant asymmetry of cyber weapons has always been the main driving force for the United States in pursuing offensive capabilities”. According to the report “Great-Power Offensive Cyber Campaigns: Experiments in Strategy” [13] released by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) on February 24, 2022, the New York Times also reported in 2013 that “Obama authorized cyberattacks on North Korean assets to strengthen the coercive strategy, which has been strengthened for more than a decade but has not achieved the expected results. After 2013, this new measure added cyber or electronic attacks in the stage before North Korean missile launches, which caused some North Korean tests to fail”, and believed that the relevant evidence was highly reliable.

In addition, in January 2021, the Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan (CNO NAVPLAN 2021) [14] explicitly stated that “when a conflict occurs, the Navy’s special forces are often the first to arrive on the scene and can rapidly expand their forces to control the sea and project power to the shore. After the hostilities are over, they will continue to maintain forward deployment and safeguard the long-term interests of the United States through continuous forward engagement”. “The Navy’s power projection and influence range is broad, including both launching attacks on enemy forces and shaping the battlefield situation long before the time of combat, letting competitors know that they have no viable means to achieve their objectives”. From the 2024 fiscal year defense budget overview [15] released by the U.S. Department of Defense in March 2023, “$5.8 billion of the budget is used to disable adversary missiles or conduct pre-launch jamming activities”. The U.S. military has been committed to disabling adversary weapon systems to reduce its own risk factor; on the other hand, since 2012, it has also been working to avoid weapon systems from having vulnerabilities that can be attacked by cyberattacks as intelligent and software-defined weapons have accelerated their evolution. U.S. Department of Defense testers spare no effort in searching for cyber vulnerabilities in all of its weapon systems under development, and commission the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to conduct cybersecurity assessments of weapon systems to identify factors that could lead to security problems, compile a list of vulnerabilities in weapon systems, understand the status of weapon systems with cyber resilience, and issue targeted corrective measures.

In summary, the U.S. has systematically strengthened cybersecurity for its weapon systems in areas such as policies and systems, standards and processes, technology and engineering practices, personnel and organization, and exercises and cooperation. The U.S. measures have distinct characteristics: First, they focus on the security of weapon systems throughout their entire lifecycle, covering all stages from design, development, procurement, deployment, maintenance to decommissioning, comprehensively strengthening cybersecurity protection and effectively reducing the exposure surface for any potential cyberattacks; second, they base their efforts on cybersecurity technology, creating a situation where technology, systems, and personnel are developed in parallel; and third, they emphasize mission-oriented support, correctly positioning the relationship between cybersecurity and weapon effectiveness, with the core objective of ensuring that weapon systems can still complete their combat missions even under cyberattack conditions. Typical technical measures include: (1) At the system architecture level, promoting the implementation of security architectures such as zero trust in the combat network and conducting pilot projects in the theater command and control system and joint combat network; (2) Promoting the intrinsic security capabilities of weapon systems, introducing security mechanisms such as “Secure Boot”, realizing firmware integrity protection and security updates, embedding industrial control systems and weapon platform bus security measures, and strengthening system security and embedded and platform protection capabilities; (3) Strengthening tactical data links, deploying continuous monitoring and situational awareness in the combat network and weapon system support network, and enhancing command and control and battlefield network security; (4) Requiring weapon system related software to adopt static/dynamic code analysis, secure coding standards and mandatory code review, threat modeling and attack surface analysis and other technical measures throughout the development process to ensure the network security of weapon system software and development process; (5) Reversing the fragile situation of weapon system supply chain network security through mandatory technical compliance measures, software and hardware identification and reverse analysis capabilities and the “Trusted Foundry/Trusted Supplier Program” mechanism; (6) Building a highly simulated “weapon system network range” to test the weapon system’s offensive and defensive confrontation capabilities in training and combat environments. These methods are also of reference value to us.

7. Several Reflections

(1) From a geopolitical perspective, this action is inevitable as a neo-Monroe Doctrine of Trump.

Professor Zhang Wenmu of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics noted in his article “Trump’s New Policy and China’s Opportunities”[16] published in August 2025 that “Trump’s new policy is a defensive strategic contraction and is returning to the Monroe Doctrine”. “The essence of the defensive strategic contraction is the forced adjustment of the United States in the face of the “East Rise and West Decline” pattern and its own economic decline, marking the structural loosening of the US imperial global hegemony system”. On December 4, 2025, the US government released a new version of the National Security Strategy, marking a major strategic shift, clearly shifting the core national security interests from great power competition to the Western Hemisphere, and consolidating its base in the Americas. This also verified his judgment. The characteristics of the strategic contraction period of imperialist countries are that, in the context of insufficient resources to support global hegemony, they will forcibly delineate a core interest circle based on local geopolitical expansion. At this time, countries outside the circle may be abandoned or actively alienated; but at the same time, it is also necessary to see that the intensity, frequency and breadth of their use of power against countries within the circle will be further upgraded and strengthened. Similar to the collapse of a star, some matter escapes its gravitational pull, while others rapidly collapse and compress towards the core, maximizing the density of matter in the core region within a very short time. Therefore, in the face of the strategic retrenchment of America’s neo-Monroe Doctrine, we must recognize both the vacuum created during this retrenchment period that is beyond the reach of the US and the need to build a more robust foundation of power control within the redefined boundaries of its core interests. Actions taken within this framework will be an intensification and escalation beyond historical limits, frequently breaking conventions and crossing red lines.

A crucial step in implementing the neo-Monroe Doctrine strategy is to “clean house” in the Western Hemisphere, purging anti-American nations in Latin America, overthrowing their legitimate governments, and installing pro-American puppet regimes. Venezuela is the largest pivotal country on the southern coast of the Caribbean, and controlling Venezuela is crucial to controlling the Caribbean and subsequently the Gulf of Mexico. This invasion of Venezuela bears the distinct imperialist and power-driven characteristics of the US’s historical invasions of Grenada, Panama, and other Latin American countries, and is also very much in line with Trump’s calculating style, demonstrating the Trump administration’s new military characteristics: resistance to great power war and fear of the quagmire of interventionism. However, by carrying out a “decapitation strike” through rapid and relatively low-cost “special operations”, the US can achieve regime change in an anti-American country, avoiding the quagmire of war that might have resulted from previous US interventionism, while simultaneously asserting its sphere of influence. Given this choice of a more cost-effective approach aligned with US strategic interests, the Trump administration may exhibit a stronger adventurism than other presidents. Therefore, despite the extremely sudden nature of this incident, the strategic contraction of the neo-Monroe Doctrine in the United States, coupled with Trump’s adventurist military decision-making style, constituted to some extent the inevitable elements of this operation.

(2) Venezuela failed to make extreme preparations based on a bottom-line mentality, which created an opportunity for the US to carry out its actions.

Judging by the effectiveness of U.S. operations, the Venezuelan government lacked corresponding bottom-line thinking in its assessment and response. Regarding U.S. military actions—including targeting President Maduro himself for direct capture—Venezuela demonstrated insufficient strategic judgment and inadequate preparations. Compared to other Latin American countries that have faced US intervention, Venezuela is not an island nation like Grenada, but a country with over 900,000 square kilometers of land and considerable strategic depth. However, Venezuela’s capital and other important cities are located near the coast, which provides a significant advantage in economic development, but puts it at a severe disadvantage in the event of military confrontation. Under the escalating threat from the US, Venezuela failed to effectively utilize its strategic depth by relocating its leaders and command structures to a more geographically distant region for war preparations, largely maintaining its existing routines and operations. It is evident that Venezuela assumed the US was still employing its traditional “pressure-driven change” approach, failing to anticipate a direct, surprise kidnapping operation. Venezuela’s strategic assessment of the inevitability of US actions was flawed. Against the backdrop of a general strategic retrenchment by the US, with a greater focus on Latin America, financial capital is already proactively adapting. For example, Warren Buffett has consistently increased his holdings in Chevron, the only major US oil company with operating rights on Venezuelan soil. This clearly demonstrates that US financial capital is preparing to overthrow the Maduro government and propel Venezuela into a new form of economic colonization, but Venezuela has not yet fully completed the necessary strategic mobilization preparations.

In our previous analysis of the 2019 Venezuelan blackout, we saw that Maduro demonstrated governing ability and political resilience in the face of conflicts launched by the Western-backed opposition, including Guaido, defeating the US-backed Guaido and forcing the new opposition figure, Edmundo González, to flee to Spain in 2024. However, it is highly likely that the US will also believe that relying on the traditional, existing paradigm of color revolutions that incite internal unrest against the current Venezuelan government is”not a viable path”. The US may temporarily abandon this option and shift to higher-intensity military action. Venezuela has long lacked sufficient accumulation and preparation in national power mobilization and military struggle; when faced with significant risks, its judgment of bottom lines is inadequate, and it lacks the capacity for maximum organization and mobilization. This further leads the US, with its comprehensive power advantage, to believe that it can continue to push the boundaries without serious negative consequences. But this is precisely the complexity of the struggle for national independence and the process of developing autonomy in Third World countries. In August 1964, when Chairman Mao Zedong met with a delegation from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Venezuela at the Great Hall of the People, he pointed out that “the goal of the revolution is very clear, but the methods of fighting against imperialism and its lackeys will become clear gradually. It is impossible to become clear in a day or a year”.

(3) Cyber warfare continues to evolve from a supporting factor to a dominant factor in the course of warfare, and will ultimately undergo a sudden change in the era of artificial intelligence.

As cybersecurity professionals, we are aware of the value of our work. However, based on the objectivity and rigor required for national security technical support, we also oppose exaggerating the impact of cyber threats through a “crying wolf” approach. In peacetime, cyber warfare has gradually become a dominant force, from continuous intelligence gathering supporting strategic initiative to manipulating public opinion and shaping perceptions. These are all adversary activities that we need to pay close attention to and guard against. However, in wartime, cyberattacks remain a secondary force. Their core role is to provide intelligence, cover, and “open channels” for traditional military operations (firepower strikes, special operations, etc.), rather than undertaking core combat missions independently. As cybersecurity professionals, we are aware that the impact and effectiveness of operations depend on the “capability gap” between the attacker’s cyberspace operational capabilities and the adversary’s defensive capabilities. The resulting effect is highly proportional to the attacked party’s dependence on cyberspace. This can only be mitigated through systematic defense capabilities. And as society becomes more deeply reliant on digital and artificial intelligence systems, cyber warfare will one day become an even more revolutionary and dominant element of warfare. Therefore, every country that is accelerating its development and progress through digitalization and intelligentization needs to build cybersecurity capabilities that are commensurate with its level of development in order to safeguard its future.

References

- DOW: Trump Announces U.S. Military’s Capture of Maduro. 2026.

- Will Merrow, Mapping the U.S. Military Buildup Near Venezuela. 2025.

- https://www.cfr.org/article/mapping-us-military-buildup-near-venezuela.

- Antiy: Preliminary Analysis and Reflections on the Large-Scale Blackout in Venezuela. 2019.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/VeauL3WQE5dQsQP0huBl7w

- National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center (CVERC). Analysis Report on the “Second Date” Spyware. 2023.

https://www.cverc.org.cn/head/zhaiyao/news20230914-erci.htm

- Retrospective Analysis of the Equation Group’s Attack on SWIFT Service Provider EastNets. 2019.

https://www.antiy.com/response/20190601.html

- Xinhua News Agency. International Observation – Brazilian President Surveilled by the U.S.: “The Surveillance Empire” with a Long Trail of Misdeeds. 2024.

https://www.news.cn/world/20240725/f12a98ebec654404aad015a80909a9a4/c.html

- US Joint Chiefs of Staff: Joint Cyberspace Operations. 2022.

- Rand: Open Source Inteligence (OSINT) for the Defense Enterprise. 2018.

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1964.html

- Antiy. “Analysis of U.S. Cyberspace Attack and Active Defense Capabilities” (12-Part Series). Cyberspace Security & Military-Civilian Integration. 2017(12)-2018(11).

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/PnaYXZ9snK6fv_lgCFszDw

- Antiy. Antiy’s Analysis of U.S. Cyberspace Attack Activities: Compilation of Findings (Part 1) – Sample Analysis Chapter. 2022.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/XTe1WlaGGE-x_3c7FJz6dw

- Maren Leed: OffensiveCyberCapabilitiesattheOperationLevel. 2013.

- IISS. Great Power Offensive Cyber Campaigns. 2022.

https://www.iiss.org/research-paper/2022/02/great-power-offensive-cyber-campaigns/

- DoD: CNO NAVPLAN 2021 – FINAL. 2021.

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jan/11/2002562551/-1/-1/1/CNO%20NAVPLAN%202021%20-%20FINAL.PDF

- DoD: FY2024_Budget_Request_Overview_Book. 2024.

- Zhang Wenmu. Trump’s New Policy and China’s Opportunities. Journal of Minzu University of China, No. 4, 2025.